Why You Should Try Science Communication During Your PhD

SciComm can be great, even at a PhD level. Here's why.

Why You Should Try Science Communication During Your PhD

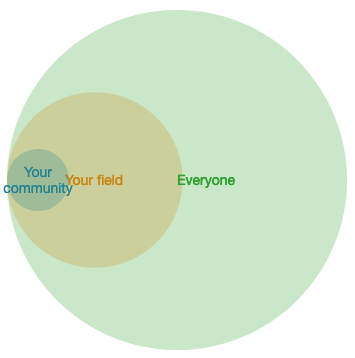

Communicating our work is a big part of being a researcher - writing papers, presenting posters, giving talks, even just office brainstorming is communication after all. But often it’s quite limited in the sense that normally we aim to talk to people that are well versed in our topic or at least our field. As an example, in RL papers or talks few people explain the details of the standard RL problem formulation and how the algorithm they use as a baseline tries to solve it, they instead talk about the parts that are relevant for their approach. Maybe they use a different setting than the standard MDP or develop an extension for DQN and thus to help people understand that novel aspect, they recap the connection points to the literature. And that’s good, I think trying to do anything else in a conference or 15 minute presentation will waste a bunch of people’s time, in such a setting we expect people to have a basic understanding of common concepts. I just think that it can be a really good experience to get out of these settings and talk to a broader range of people. Take a look at this (very professional and very accurate) Venn diagram I drew up: How many of the categories of people do you tell about your research (Let’s not count Mum, Dad and Grandma here)?

I talk to people working on the same topic as me a few times a week, update a wider circle every few weeks informally, give internal presentations multiple times per year and then have a handful of conferences and/or workshops in there. Maybe one or two occasions per year will have me explain what I do to someone not working on ML topics directly but at least invested in computer science in some way. That’s already quite a bit, I think, and it’s because my group has solid workflows around presentation and also because I tend to enjoy talking research. Until this year, however, I didn’t really have many opportunities to speak outside of research settings and after I did, I noticed it’s definitely something else. It’s hard, time-consuming and has little direct payoff. I really like it, though, and think you should try as well, even (or maybe especially?) during your already stressful PhD. In this blog post I want to outline why I think that and give you some ideas for things to try that shouldn’t take too much effort and are pretty much free.

What is Science Communication?

Wikipedia says “Science communication encompasses a wide range of activities that connect science and society. Common goals of science communication include informing non-experts about scientific findings, raising the public awareness of and interest in science, influencing people’s attitudes and behaviors, informing public policy, and engaging with diverse communities to address societal problems.” - and actually a lot more than that. What’s important though: we’re not talking to experts, we’re telling everyone else what we’re researching.

That can come in many forms, you could show a robot off to third graders, give a presentation at a business conference, write a newspaper article or even take part in a podium discussion at a public event, all of that is Science Communication. If you look for #SciComm on social media, you’ll find tons more examples. And obviously it’s important to keep non-experts updated with research, climate change is a great example here. But that’s very large scale and should be done by professors, science journalists or even scientific organizations. It’s not a field for PhD students, right?

Why should you actively look for SciComm opportunities?

There’s two ways to understand this question. The first is “What can other people take away from my research, I’m just a PhD student?”. And I think the answer is “more than you think”. Yes, most PhD students work on super specific questions - but you’re doing it because you think I’ll make a difference in the grand scheme of things, right? I think if done well it might actually be more interesting to hear about one specific idea than get an overview of a whole field simply because the whole field will be much harder to grasp, especially without a lot of background knowledge. Getting deep into one detail, though, is totally possible for the audience if you break it down far enough and then they might feel like they actually understood the core of it. I know I’d certainly prefer to learn about one specific detail of, let’s say carpentry, than someone trying to give me a rough overview of all techniques – that would just leave me confused, most likely.

The other implication of the question is “But why do I have to be the one, can’t someone else do it? What’s in it for me?”. To a degree that’s true, you won’t be rewarded for giving a general public presentation in the same way you would be for giving an academic one (in terms of new connections, feedback, exposure of your work…), plus it’s a lot more work. But I think making your topic understandable for anyone is a great skill to have. It’s a lot about storytelling, finding everyday analogies, about trimming down the details until you’re left with the core idea of your work. I never had to do this before and the first time it was hard and took a lot of time. Then it got easier. And I notice how it’s useful in academic contexts as well since you won’t often have enough time to explain all the details of what you do.

Think of it this way: If you can give an elevator pitch to a 15 year old, you’re probably going to give excellent ones to people you meet at the next conference. If you can come up with an interactive demonstration of your research for a science fair, finding illustrative examples for your next paper will be easy. Communication is a skill and SciComm is communication in hard mode. It can give you great practice along with your research skills for future grant applications, networking and even job hunting.

Maybe even more importantly: SciComm forces you to focus on what you’re actually trying to accomplish. What’s the end goal here? How will others interact with your research in 10 to 15 years? If you want to, you can escape these long-term questions as a PhD student, but further along in your career you’ll need to have this kind of plan and be able to convince others that it’s worth working towards. Even if a general audience might not be able to understand the nuances, their questions and reactions can help you find out what topics are important and what others are concerned about. It lets you step outside of your bubble for a bit and refocus on what matters beyond the next paper. I find that’s great motivation for future endeavors.

What can you personally do?

In lieu of someone asking you to take part in a larger initiative, you can always take part in scicomm events or organize them yourself. The German site “wissenschaftskommunikation.de“ lists many different ideas for formats - unfortunately it seems like this part of the page isn’t translated to English (so you might want to use the translation tool of your choice). Here you can filter by who you want to target and what kind of format you prefer. I recommend taking a look even if some things (like making a video game) might be out of reach for now.

Some of my favorites are science slams, science pub crawls and science nights. As you can probably tell, they all have one thing in common: usually they take part in the evening. The important thing to me, though, is the relaxed atmosphere you can create with all three of them and that they’re fairly low effort for organizers and participants. So what are they exactly?

-

A science slam is similar to a poetry slam: around four or five participants get 10 minutes each to speak and then the audience scores the presentations from 1 to 10 (this is usually done by distributing pens and a few sheets of paper, then asking the audience to settle on local scores). Instead of a slam poem, however, the task is to talk about one’s own research in an accessible and entertaining way. Here’s a (German) video of me doing one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQ4y5ovvp2Y This is really challenging because the crowd is drinking beer, wants a laugh and you’re trying to get across something that can take months or years to understand the details of, but that’s exactly the fun of it. Winning or losing doesn’t really matter since the scoring is pretty unfair anyway, it’s about fun, not about the contest.

-

Science pub crawls are somewhat similar as they take place in pubs or other places meant for drinking in the evening, but here there are a few different pubs and each scientist or group of scientists get one. Here you can give people a short pitch of your work and then discuss their questions and ideas. This is much more interactive, but still quite hard since the technical equipment is probably limited.

-

A science night on the other hand can mean many things, but often they’re organized at universities, so you can keep all your fancy stuff at hand. Often there are many different offerings in the form of talks, experiments, hands-on demonstrations and so on near each other and people can just walk around and see what they’re interested in. It’s a great opportunity to test demonstrators, especially if they’re supposed to be hands on, and you meet a fairly mixed audience with many children. That’s a different kind of challenge altogether and you’ll be tired afterwards, but it’s really rewarding because people are often very interested in the specifics of your research.

Obviously these are only the three I like and think are somewhat feasible in an academic context with limited resources. With more time and money, the sky’s the limit. For example, I recently met someone at a workshop who is working on designing an exhibition in a big German museum for a research cluster that successfully requested a position for museum work in a grant proposal. In the same workshop, someone else curates a newsletter for teens, a third does technology chats with older people over coffee and cake. Or maybe a podcast works better for you? Either way, experimenting with SciComm at least once is in my opinion a great way of practicing presentation skills while making what you do more accessible.

What really stuck with me was the introduction to the workshop I mentioned by Prof. Wolfgang Heckl who is the general director of the Deutsches Museum in Munich. He said: „We do science communication because we like people and we want them to take part in scientific advancement“. And why else do science in the first place?